⚡️ The French officer corps came out of the Great War all grown up?

Although there are many links between memory and history, "memory does not tell the story...it tells the questions that society, at a given moment, asks itself about its history...1". 1 Thus, different groups "bearers of memory" defend their own vision of the historical fact. The historian, for his part, seeks to step back from this sometimes painful awakening of memory, carried by memories that seek recognition in the present of their vision of events.

The historian tends to reconstruct the past as objectively as possible. He relies on a critical study of sources, whether written, oral or archaeological. Memory and history therefore differ in the type of questions addressed to the past. Memory wants to rehabilitate, to "save from oblivion", whereas history wants to understand and explain the past in an objective way.

Today, when it comes to the First World War, memory refers to the courage of the poilu, but more rarely do we hear the names of generals and marshals, on whom, moreover, we make unqualified judgments. Thus, memory tends to make incompetent generals and marshals who are cautiously kept out of the front lines, hence the term "hiding". History seems, at first glance, to agree with them.

Indeed, in August 1914, Marshal Joffre received authorisation from the Minister for War to exclude leaders he deemed incapable. Joffre relieved two out of seven army commanders, nine out of twenty-one corps commanders, thirty-three out of seventy-two division commanders, one out of ten cavalry division commanders and more than ninety brigade generals. 2 !

It would be easy to deduce from these statistics the widespread incompetence of the French High Command. However, at the end of the war, Marshal Foch had a survey carried out in order to draw up a list of generals "killed by the enemy" between August 1914 and July 1918. The latter brought to light the names of forty-one generals. But this list was incomplete.

If we consider the general officers "killed by the enemy", two more are added to this initial list 3. Finally, if we now evaluate the corpus from the perspective of the attribution of the mention of "death for France" . 4 "This figure, which is used as a reference for assessing the total losses of the Great War, must be practically doubled to ninety-six individuals, and even to one hundred and two if we count the admirals and assimilated stewards. 5.

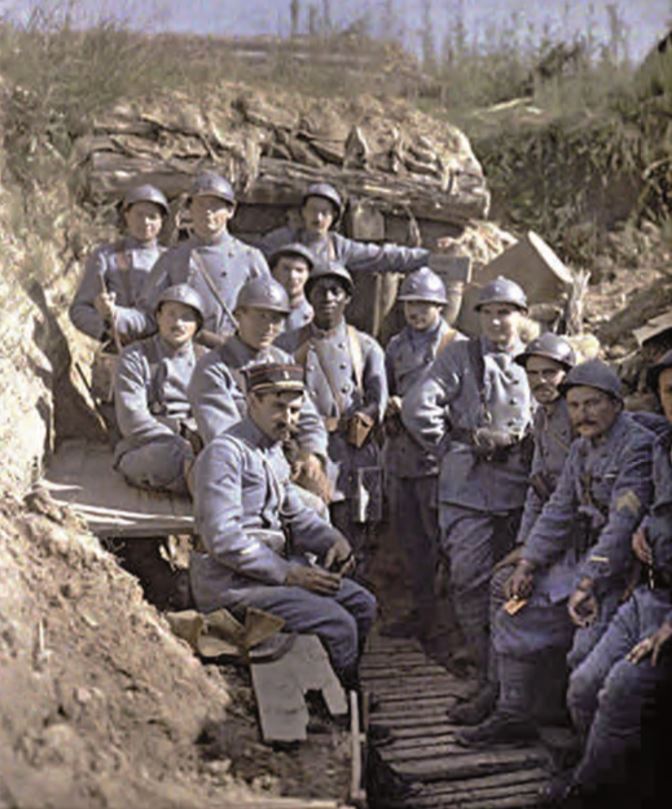

The historical truth is that the officer corps paid a proportionate, if not comparatively, higher tribute than the troop. On 22 August 1914, the bloodiest day in French history with 27,000 dead on the battlefield of the Western Front, the casualty rate among officers fighting ants exceeded 30% in some units. On 31 December 1915, there were already 564,110 men killed on the Western and Eastern fronts, including 16,297 officers.

From 1914 to 1918, the army had nearly 195,000 officers in its ranks, supervising 7.9 million mobilized men. 6. In 1920, officer losses were estimated at 36,593 killed, missing, wounded or sick during operations. 7...while the number of troopers is estimated at 1.4 million. Although one must always be careful in handling numbers... 8The loss rate for officers can be estimated at 18.7 per cent, while the loss rate for non-commissioned men is 17.7 per cent.

This is a far cry from the bad example set by management. These figures defeat another legend about the relationship between the men in the trench. "All hairy, but not all equal." No doubt, at the beginning of the conflict, the officer corps was socially different from the troop. This situation naturally led to a demarcation of the two entities that was quickly called into question for two obvious reasons.

Firstly, the erosion of managers, which we have just discussed, leads to internal promotions that create a significant social mix. Secondly, the experience of the front line is forging an identity that is superimposed on the class identities, or professions of the civilian world. We soon see the creation of a fighting community.

A large number of hairy letters refer to the comradeship which unites men without distinction of rank. Maurice Genevoix expresses this camaraderie between the head of contact and his men. In his correspondence 9The hairy one tells these small gestures, these small attentions: "a joke, a cigarette" which puts the man in confidence and makes obedience easier for the officer. 10.

According to Rémi Porte, "it is therefore, in the end, the consideration that the superior gives to subordinates that motivates the soldiers". Moreover, we are united by the same fate, under the same conditions, which brings men together. As the conflict progressed, a new hierarchy emerged: the authority of seniority, symbolised by the V-stitched presence chevron on the sleeves of the uniforms after a year at the front, of the same size and colour for both men and officers.

In fact, there would be much to say about the relations between the troop and its leadership during the indiscipline that raged in 1917. It did not come out of nowhere. In the course of the conflict, several warning signs thwarted the idea of a unanimous army driven by patriotic sentiment. All specialists agree that the failure of the offensive on the Chemin des Dames was not the only reason for insubordination.

In 1917, the movement followed the disappointment felt following the failure of an offensive perceived as decisive and the extent of the losses suffered. They refused to take part in new attacks that were deemed useless. This phenomenon is not new in the French army, the revolutionary and even imperial armies did not escape it.

However, however numerous they may be, it is striking to consider that mutineers never attack their contact cadres, but always at the highest level of command. It is therefore not "the hierarchical military principle as such that is targeted through the movement of refusals to obey, but the expression of a fundamental separation between those who order, without verifying the feasibility of their orders on the ground ... and those who wage war". In reality, the division is made between those who make war and those who administer war. 11.

Not only are the contact officers not taken to task, but the soldiers want to continue to hold the front line. This insubordination is therefore relative. In 1813, when the remnants of the imperial army flowed back from Leipzig onto the Rhine and were now on French soil, in the minds of the fugitives there was no question of holding on to the banks of the river, but of returning to their homes!

In 1813, the soldier remained deaf to the exhortations of his entourage and deserted en masse. During the Great War, the soldier respected his officers and it is recognised by all historians that desertion in France was quantitatively marginal and that it did not influence the course of the war.

The same applies to the notion of offensive. In the aftermath of the hecatombes experienced by the French armies during the first weeks of the Great War, the observation that dominates the minds of a large number of observers is that of a failing high command that was the victim of bad doctrine: the excessive offensive. 12. However, there are some nuances. First of all, this mode of action was shared by all the foreign armies of the time and was not a Franco-French phenomenon. The latter can be explained rationally, moreover, by the teachings and the trauma born of the War of 1870, largely due to a strictly defensive doctrine.

In 1870, the French High Command decided to wage a defensive battle on favourable terrain chosen in advance. This doctrine ultimately resulted in a static battle that gave the Germans complete freedom of action, allowing them to manoeuvre in the intervals and establish favourable power relations in each of their decisive actions.

On the other hand, the doctrine of the over-zealous offensive was singularly tempered by the regulations of the time, which took into account the notions of security and intelligence, or the need to manoeuvre, such as the need to protect oneself from fire. These "regulatory" notions are opposed to an army whose officers would be fanatics only responding to the call of assault. Finally, the cult of the offensive is dominant among many military leaders, but is also shared by politicians.

In his book on the history of the French army 1914-1918, Rémi Porte evokes John Horne's words that "the notion of offensive" is "the most important thing to remember about the French army. is, from 1915 onwards, justified at all levels of the hierarchy, as well as at the rear, by the situation of the French army:"For the soldiers, as for the generals, trench warfare obeyed the political imperative that had prevailed during the crisis of July 1914 and thethe entry into the war, that of National Defence against an aggression attributed to the Germans... it was a sort of confirmation of the victory of the Marne. However, the essential counterpart remained the offensive; it was the only way to drive the enemy out of the national territory and free the soldiers themselves from their obligations. Hope for survival - both national and personal - and the future were combined in a temporal framework where everything depended on the victorious offensive.

This notion of the offensive is therefore not exclusively the will of the command. Lieutenant-Colonel Porte cites the example of Auguste Allemane, a reserve officer, who before the war exercised local responsibilities at the Bordeaux town hall. He wrote on 23rd March 1916: "It is not by resistance alone and the abandonment of some ground at each attack that one can achieve the desired goal. Whatever the price, and it will be high, luck can only be reversed by our own attacks".

Moreover, the press, both national and local, maintains this state of mind. April 6, 1917 13It is, moreover, the politicians who, by interfering in a specifically military area falling within the remit of the Commander-in-Chief, accept the principle of a new offensive, which is far from unanimously accepted by the senior military officials present (Castelnau, Pétain, Micheler and Franchet d'Esperey).

In conclusion

In 1914, the officer corps fully met the political objective. The latter, supported by the whole country, was betting on a short war that the army had to win by its bravery, morale and combativeness. Achieving this objective is concretely expressed by the stated will to practice a war of movement. The realization by the leadership, that the power of defensive fire is such that the principle of an excessive offensive is no longer tenable, gradually leads it to orient the doctrine towards a war of positions.

During the four years of conflict, the adaptation shown by the high command is therefore undeniable. Today, it is all very well to blame it for a lack of agility. We forget the importance of the obstacles of that time: the mass, represented by the millions of men involved, the inordinate vastness of the battlefield and the poverty of the means of communication.

The victory of 1918 was in France, the result of the commitment of all the resources of the nation. From the government, embodied by Clemenceau, to the people in the rear and the woman who played an essential role 14, through industry, the Empire and of course the soldier, commanded by valiant leaders.

___________________

1 François Cochet, Rémi Porte, Histoire de l'armée française (1914-1918), la première armée du monde, Tallandier, Paris, 2017.

2 Hervé Coutau-Bégarie, Politique étrangère, année 1982, volume 47, N° 3, pp. 757-759, which refers to Pierre Rocolle's work, L'hécatombe des généraux, Lavauzelle-Paris, Limoges-1980. The Minister of War, Adolphe

Messimy (1869-1935), authorized General Foch to exclude leaders he deemed incapable. A total of 162 generals

are relieved of their duties.

3 François Cochet, Surviving at the Front (1914-1918), les poilus entre contrainte et consentement, Soteca, Paris, 2005.

4 It is specified that the mention "dead for France", which results from the law of 2 July 1915, is granted to any soldier killed to the enemy who died of war wounds, or to any soldier who died of illness or during an accident on duty.

5 Article by Madame Julie d'Andurain, La voie de l'épée, blog by Michel Goya, 18 February 2014.

6 Empire included. Source: figures from Jay Winter, The Great War and the British People, quoted in Stéphane Audouin-Rouzeau, Jean-Jacques Becker, Encyclopaedia of the Great War, Paris, Fayard, 2004.

7 Including 4,848 Saint-cyrians. Some promotions were wiped out. That of "from the cross to the flag" (1912-1914) lost 310 Cyrards out of 535 (58% of its strength). Golden book of the Saint-cyrians who died for France during the Great War.

8 Indeed, among the mass of men mobilised, a certain number of them, appointed as officers during the conflict, died.

9 A very considerable number of letters can be consulted at the SHD.

10 Maurice Genevoix, Ceux de 14, Flammarion, Paris, 1949.

11 In Captain Conan, the hero explains: "There are those (sic) who make war and there are those (sic) who win it! ».

12 Real errors of command nestle where they are not expected. Thus, bringing the survivors back to the same battlefields where death had spared them proves to be catastrophic for morale. According to Maurice Genevoix: finding the same objects of miserable horror again and again from one relief to the next was undoubtedly more terrible than facing up to danger again.

13 Meeting of the French War Committee in the train of the President of the Republic under the chairmanship of Poincaré. The latter brings together military and politicians. The essential debate focused in particular on the decision to give carte blanche to Nivelle, who was in favour of a new offensive.

14 In addition to the professional or voluntary nurses, who worked in the infirmaries, field hospitals and large hospitals in the rear, women replaced the men who had been working in the infirmaries.women replaced the men in the factories, mainly in the food and arms factories, where they prepared soldiers' rations and produced the cartridges, shells and rockets that were sent to the front. In the countryside, many of them replaced the men in the fields.