Principles and cultures of war

A questioning on the principles of warfare adopted by the French army cannot avoid a study on those that the other great military powers set themselves.

The differences observed are in fact evidence of the research, which has a more operative purpose. Fuller, also influenced by the writings of the Welsh general Lloyd in the early 18th century, focused on the study of Jominian principles, retaining to From 1921 onwards, the principles of direction,offensive, surprise, concentration, distribution, safety, mobility, endurance anddetermination were retained. Foch, for his part, had previously sought, from the end of the 19th century, to identify "hyper-principles", while demonstrating the same Clausewitzian reserve, as to the definition of immutable laws of war. He thus confined himself to stating the principles of economy of forces, freedom of action, free disposition of forces and security, which he felt should be applied in a variable manner, taking into account the ever-changing circumstances of war.

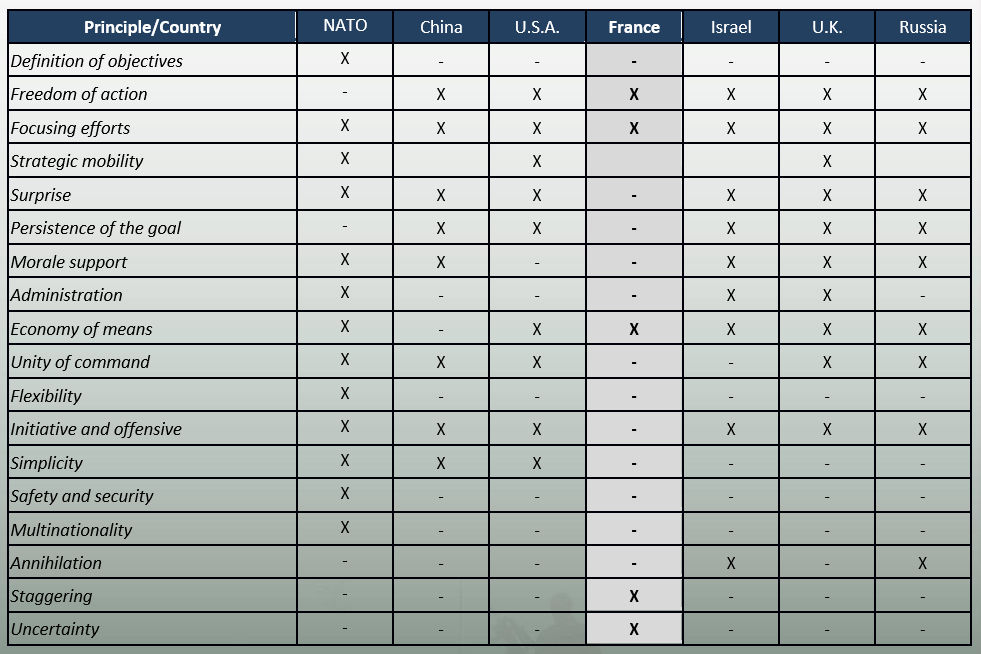

A study of the table below shows that there are significant differences between the various armies, but also convergence on certain principles (freedom of action, surprise andconcentration of effort) among Westerners , while the Russian, Israeli andChinese lists differ markedly from this European influence. TheClausewitzian influence is thus noticeable in Germany, which remains today the only major military power that has never adopted a list of principles.

This influence can also be found indirectly in the limited number of principles that still characterize French doctrine today. Conversely, theJominian exhaustiveness constitutes , under Fuller's influence, the hallmark of the Anglo-Saxon schools of strategic thought. Thus we find a list of ten principles in the current British doctrine, while the Americans have retained nine. Very much influenced by Jomini, then by Fuller, the American army finds in this list a certain form of scientific management of war action, very much adapted to their Taylorian approach to the resolution of complex problems. However, this exhaustiveness raises the question of the distinction to be made between principles and procedures. Should flexibility, offensive and annihilation, for example, be considered as principles or procedures?

Apart from this differentiation in the number of principles adopted by each school of thought, the evolution of the material conditions of war, and therefore of the methods of application, constitutes a second variable which conditions the reflection on the laws of war. The question of the timelessness and intangibility of principles, as well as their link with their application procedures, are therefore major questions for most contemporary strategists. Hervé Coutau-Bégarie thus wondered about how to determine to what extent the appearance of new processes gives rise to an adaptation or a break with established principles" . For the doctrines of the Jominian thought, the conjunctural modification of principles is obvious.

Thus, on the strength of his experience drawn from the Second World War, Marshal Montgomery developed Fuller's initial principles into the list still adopted by the British Army today. Considering that this list was "neither infallible nor immutable ", he remained convinced that the principles needed to be adapted to the technical conditions of the "new wars". Many Western strategists, including the military historian John Keegan, thus consider that powers must continually adapt their principles to the technological environments and engagement contexts of their times. As a result, in 1990, the US military introduced a new list of principles for operations other than war, including legitimacy, perseverance, and restraint.

Thus, thinking cannot remain static. However, as Hervé Coutau-Bégarie pointed out, "the historical conservatism of the military institution often comes from the fact that it establishes as a principle and even as a dogma what is only a process imposed by circumstances or by a necessarily changing technique" . It therefore becomes legitimate to question both the "universal" nature of these principles, but also the exhaustiveness and modernity of the principles adopted by the French. By modernity, we mean, of course, the adaptation of these principles to the conditions of conflictuality today and those envisaged in the near future.

What are the implications of the new approach to conflictuality on traditional principles and their application procedures?

The relevance of the five principles currently retained by French doctrine remains undeniable if we consider them strategically. However, are they sufficient to reason for an air-land manoeuvre encompassing all the factors characterising tomorrow's commitments? Prospective studies conducted by most of the major Western powers tend to characterise the operational environment of 2035 through several types of disruptions, particularly strategic, societal and technological, compared to our current environment. These changes do not call into question these principles, but rather their application processes and the way they are applied. the definition of new tactical and operational effects to be achieved in order to create the conditions for strategic victory and lasting peace.

As ATF's editors point out, the search for the annihilation of the adversary through a decisive battle no longer meets the political-military realities and objectives set for every operation today. Armed force alone is no longer sufficient to guarantee strategic victory, if it ever was. Armed force now makes only one contribution, essential but not sufficient, to creating the conditions for strategic victory.The armed force is now making only one contribution, albeit an essential but not sufficient one, to creating the conditions for strategic victory, i.e. a security environment that gives the political decision-maker sufficient superiority to negotiate a way out of the crisis under acceptable conditions. As the notion of a decisive battle no longer constitutes an absolute paradigm for achieving strategic victory, such crisis exit strategies are therefore today characterised by an integrated approach, which takes place over a long period of time and requires coordinated and often costly action involving a variety of players, mainly non-military.

The latter generally cannot act effectively without a minimum level of security that can only be guaranteed by armed forces. There has therefore been an increase in bilateral cooperation and ad hoc partnerships with regional/global institutions, private companies, local actors, security and defence service companies (ESSDs) and NGOs. Furthermore, the porosity between international criminal organisations, regular and irregular adversaries often having greater agility and freedom of action than the deployed forces, contributes to the imposition of more indirect, more global and no longer essentially military approaches.

Thus, the search for avoidance or the circumvention of power by a hybrid adversary, melted within the populations, calls into question the effectiveness of direct manoeuvres aimed at the annihilation of the adversary and corresponding to a Western approach and principles inherited from the 19th century. All these trends, which are likely to become ruptures in the medium term, invite us to question their consequences on Western military thinking, which has been largely based since antiquity on an ability to produce a shock effect on the adversary and to support him, both physically and morally. Indirectly, it is therefore the topicality of the principles underlying this military thinking that should also be questioned.

The findings thus naturally lead us to question the durability, or at least the adequacy, of the principles currently used to design and conduct our operations in the future. A reasonable approach could consist, on the basis of existing principles, in reasoning about methods of application, perhaps more indirect, which would make it possible to obtain kinetic and immaterial effects that are more decisive and less costly in terms of resources.

It can thus be established that the acquisition of operational superiority in the context of current or future operations could be translated or verified through decisive effects on the adversaryand on one's own capabilities. These effects would be considered in the light of the probable emergence of new, potentially disruptive technologies, the already existing porosity of the confrontation environment, the new information context and the new forms of conflictuality envisaged in the short term.

These effects could be achieved by variable combinations of principles, applied in the fields covered by the factors of operational superiority, as set out in the prospective document Future Land Action of the French Army. In-depth reflection on these future application processes is therefore now essential.